I’m not sure which is worse, a short attention span or a short memory span. The mindset we have so flavors our perceptions that two people looking at the same reality will have vastly different experiences of it. I often awaken in the middle of the night and can’t get back to sleep. According to present psychological theory, this is a classic sign of depression, and maybe it is. But what if it is perfectly natural for people? Maybe the all night sleepers are the crazy ones. Many great artists and scientists, perhaps those with restless minds, from Benjamin Franklin to Leonardo Da Vinci to Dolly Parton, do some of their best work in the still of the night.

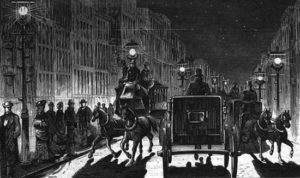

There is an historical record stretching back centuries indicating that night used to be so long, sleep was divided into two halves, first sleep, and second sleep, separated by an active time called “dead of night”. The night was not really longer, but our flavor of it has dwindled away. When I was a kid, playing hide and seek on summer nights the dark was much darker. You could completely disappear into the shadows. It was great. Then the city installed more powerful streetlights and New York became “The city that never sleeps.”

Broadway, the great white way, is so named because it was the first street lit up by Thomas Edison in 1880, considered a wonder of its time.

But what was life like before that? This is the subject of of the perspective shifting and delightful, “At Day’s Close, Night Time in Day’s Past”, by A Roger Ekirch.

Without light, there wasn’t a lot you could do, so you went to bed – early. Since clocks and the whole concept of breaking up the day into hours, minutes, and seconds was foreign to people’s experience the time was marked by events. There was twilight, shutting in, dinner, first sleep, dead of night, second sleep, and dawn.

Shutting in was important because the night was a frightening and dangerous place. People would only be out if they had to.

There was a fear of the night much greater than today. Partly this was justified by the frequent crime. Burglary and highway robbery were common, except in the American colonies. But there was also a terrible fear of the unknown which we always fill up with monsters.

Now that we have lit the night in a way that allows for no shadow, we have driven the monsters into the dark realms of space.

Ekirch illuminates a wealth of nighttime activity by mining the copious journals people kept back them, as well as court records and reports on efforts to light the darkness. Then as now money mattered. The rich could afford candles so they went blind more slowly. The poor got by on the light of the hearth and rushes, which gave off more smoke than light. There were many derisive comments in the journals about how candles made “the darkness much easier to see.” On the other hand, you can do some things in the dark quite well. One French physician advised couples that the best time to conceive was after first sleep when they “have more enjoyment” and “do it better”. Beats watching TV. Nighttime was also a time when people could escape the scrutiny and cares of the day and let their hair down. If you were willing to brave the dangers of going out, there were entertainments around for every class.

For many though, it must have been a time of great intimacy, telling stories or jokes to the few people in the house, with ties being strengthened through the long winters. If you were alone, it was a time for introspection, praying, or reading, three activities that are in decline today. If someone awakes at night now they are bound to reach for their phone and social media, the new opiate of the masses. Now, instead of tight bonds to a few, we have very loose bonds to many.

At Day’s Close is an intriguing and beautifully illustrated look into a forgotten past. For more research on sleep visit A.Roger Ekirch’s site.

I live in Romania and there are still some villages with old people living somewhere on the top of the hill just by themselves. But the younger generations leave for the city.

Yes, the city is where it is.